Getting Rid of Leisure Time

Getting Rid of Leisure Time, essay, Who are We Talking With? What Can Institutions (Un)Learn from Artists? symposium, organized by tranzit.cz, 17th and 18th May 2019, Kampus Hybernska, Czech Republic, photo: tranzit.cz.

In the following text, I focus on the topic of human

activity. In the last three years I have hit on this theme several times in

three different art projects. Perhaps for this reason I have become convinced

that a detailed analysis of human activities can answer a number of basic

questions that have surrounded various artistic disciplines for the last

several centuries. Above all this concerns the issue of social responsibility

and the openness of artistic practice and artistic institutions.

By the term "human activity", I mean all

actions that individuals or social groups perform. This includes those that are

ubiquitous, which we experience with every breath, with every movement, and

which we execute in order to satisfy our basic human needs, as well as those

through which we help those close to us or get to know the world around us.

Essentially, there are as many human activities as our languages have verbs.

Each verb refers to a specific act.

Every artistic agenda relates in some way to specific

activities. Some examples can be mentioned at random from the second half of

the 20th century – Maintenance Art Performances by Mierle

Laderman Ukeles, In Praise of Laziness by Mladen Stilinović and Lying-Down

Ceremony by Milan Knížák. In all three cases, the artists began making use

of various human activities as a metaphor to postulate new aesthetic norms, but

even more so to point out the rigidity and imperfection of the political

systems into which they were born, in which they lived, and in which they were

attempting to live out their artistic practice. Thus did they demonstrate their

social exclusion and the impossibility of fully realising their artwork as a

mother, an immigrant, and an Eastern European artist.

They demanded that their disadvantaged position in the

world of art be rectified, thus inadvertently urging for equality amongst

activities themselves, as the superiority of one human activity over another is

the cause of unequal social status between individuals and groups of

individuals.

![]()

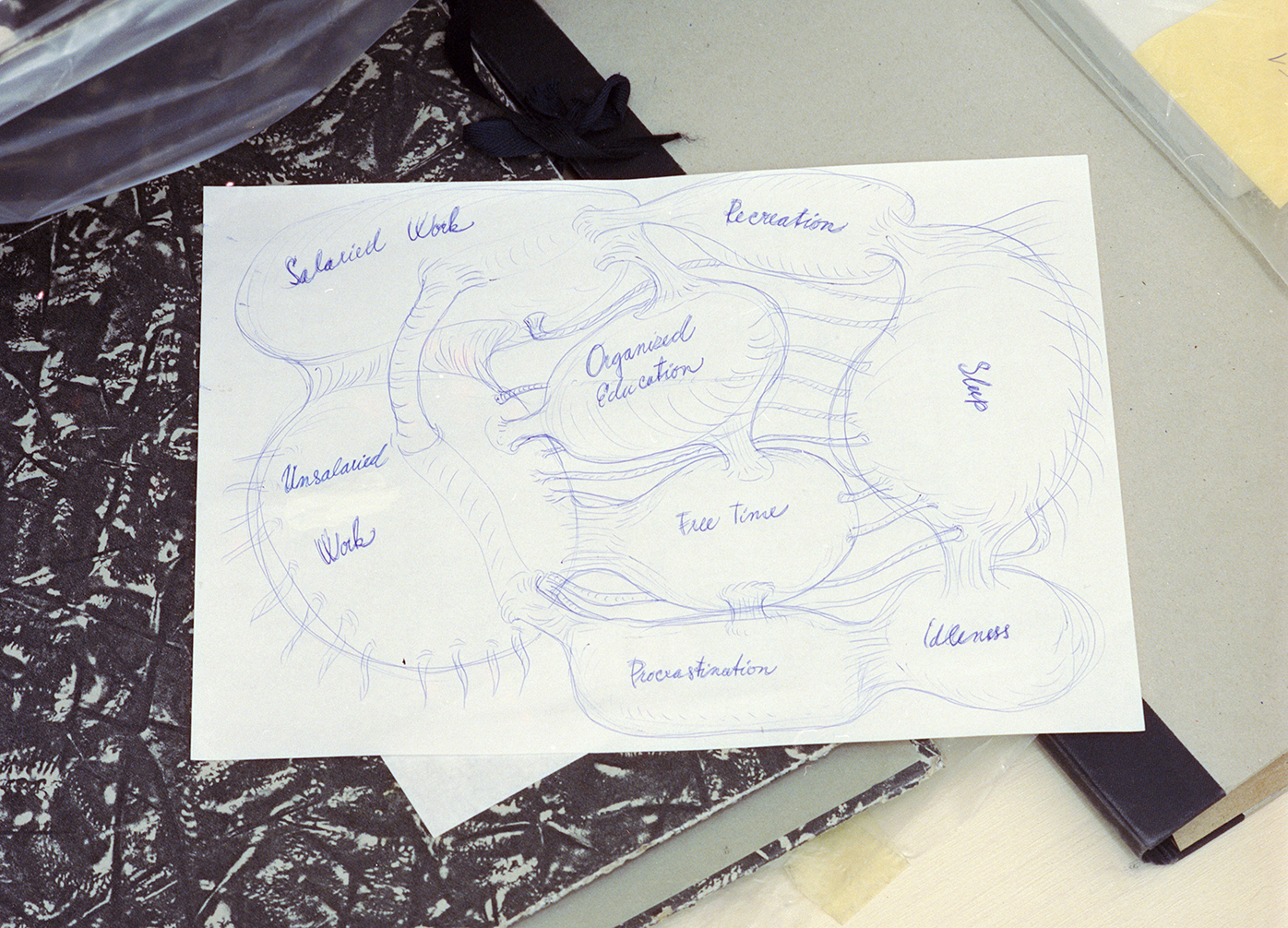

The Preparatory Sketch for a Public Autopsy of a Human Activities, 2017, 70x50 cm, Lambda print, author’s archive

I am convinced that an analysis of human behaviour can

reveal the hidden democratising tendencies in the history of art. For this

reason I would like to present two artistic studies that led me to this

specific way of thinking about art and artistic practice.

The first of these is the project Art Practice and Other Activities from 2017, in which I subjected

to analysis the majority of activities I encounter every day as a visual artist

and in which I participated voluntarily or involuntarily.

The starting point was all the data stored on several

external memory drives. I transferred all of them onto a single disc and then

divided them up by activity, either associated with artistic practice or with

regular everyday concerns. Eight items form the foundation of the archive:

Salaried Work, Unsalaried Work, Organised Education, Procrastination, Idleness,

Free Time, Recreation and Sleep.

After adding up all the data I came

to the conclusion that there are roughly twice as many items in the folder

Unsalaried Work as under Salaried Work. This means that for me to be able to

carry out my work as an artist and teacher, I must perform twice that number of

unpaid tasks. It should also be emphasised that the study did not include

activities that do not leave behind a digital footprint, the vast majority of

which we perform for our loved ones and friends free of charge.

Thanks to this monotonous clerical

work, I have to admit that I have long been neglecting vital activities to the detriment

of my artistic practice and leisure time. It was something of a cathartic

moment that changed my point of view on the institution of art.

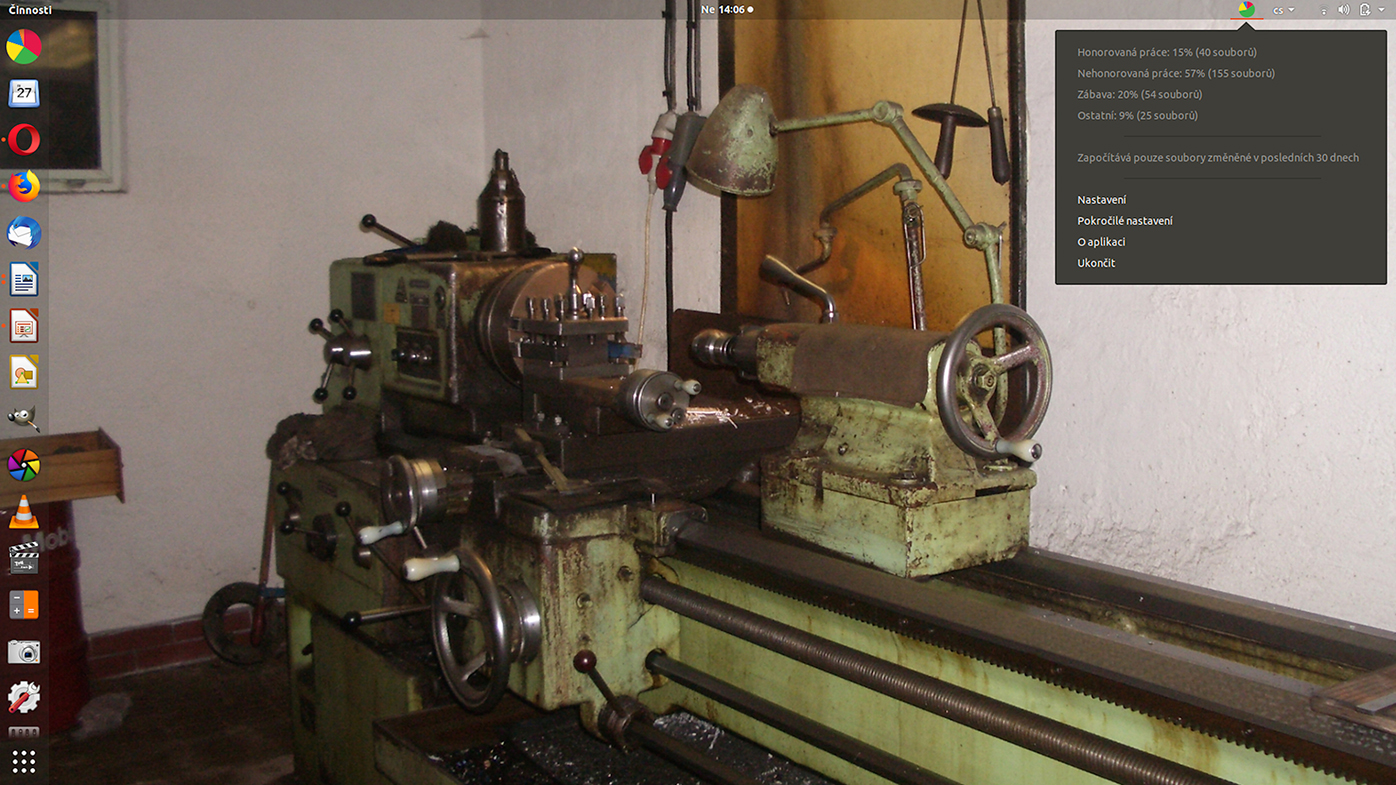

This experience ended up inspiring me to create a

software instrument entitled Human

Activities. I brought it into being by working with Jakub Valenta over the

course of last year and this one. When making it, we drew primarily on the

typology of human activities from the previous project, merely reducing the

number from eight to four.

The application allows users of the

operating systems Windows, Mac OS and Ubuntu to rename the archival folders

like Music, Pictures, Videos and Documents to the folders Paid Work, Unpaid

Work, Recreation and Other.

These can be monitored using a simple icon on the

operating system's Control Panel. When you click on it, a list of all folders

(with percentages showing their degree of usage) appears. The sum of data is

based on file size and the amount of information in the given folder along with

the time spent interacting with the data therein. In my case, the difference

between paid work and unpaid work was staggering. This time the percentage

difference was two hundred and fifty. Again in favour of unpaid work.

"It is meant for individuals who

work based on contracts, who are unhappy with their employer or who are working

on a number of part-time projects all at once. We offer those people our

software tool, thanks to which they will be able to gain greater control over

their time and space and also get a critical look at their daily interaction

with their surroundings."

We do not expect this software tool

to be successful or that those with precarious work will immediately begin

using it. It is more of a symbolic act that highlights the formal archiving of

data in digital technology and infrastructure. We are convinced that this state

reflects the value framework of employers and senior employees rather than the

needs of the average user.

![]()

Human Activities, an illustration, an application and a website (humanactivities.cz), 2019, in collaboration with Jakub Valenta, author’s archive

Both works are based on the tradition of the

emancipatory struggle for equality of various social groups. I have dedicated

myself to this topic for a whole decade. Everything began with the series of

photographs Two Families of Objects from the year 2007 and continues to

date. Over ten years I have focused primarily on the beginnings of the workers'

movements of the 19th century and their struggle for the social

equality of manual labour. In many cases workers were not fighting solely for

the societal recognition of their own work, but were also demanding equality

for domestic work and the liberation of women from the day-to-day performance

thereof.

The thematisation of "low" social activities

led to greater democratisation of society. This process was not however simple

and smooth; it was accompanied by unexpected revolutions and bloody military conflicts.

The political, economic and cultural elites were loathe to give up their

societal advantages. Both distant and recent history are thus an unfinished

story of society-wide negotiations on the meaning and status of diverse human

activities. Under the given situation, advantages are afforded to those

activities and segments of society that are able to offer society prosperity or

which are able to ignite arising crises most quickly.

For the these reasons, I gradually began to focus on

analysing human behaviour. A detailed study thereof opened up new horizons of

art history and artistic practice for me. From my own experience I can declare

that this method of interpretation helps uninitiated audiences to better

understand the inner dynamics of works of art, as they look at them from the

perspective of everyday experience, which is often based on activities that are

not consider "high" by contemporary elites.

![]()

Human Activities, a print screen, an application and a website (humanactivities.cz), 2019, in collaboration with Jakub Valenta, author’s archive